The Biden administration is considering pardons for potential targets of President-elect Donald Trump, according to a report from Politico. This report comes a week after President Joe Biden pardoned his son Hunter, who was convicted of federal gun and tax charges.

Mr. Trump has singled out members of Congress who investigated the Jan. 6 U.S. Capitol attack, telling “Meet the Press” that they should be jailed.

Why We Wrote This

As Donald Trump talks about prosecuting his political opponents, President Joe Biden could protect possible targets with pardons. Experts say America might be entering a new era of using this broad presidential power for political aims.

Some of his nominees for high-profile law enforcement positions have made similar comments, including potential FBI Director Kash Patel, who appended a book he published in 2022 with a 60-name “enemies list.”

Mr. Trump’s focus on prosecuting his opponents may be unique among incoming presidents. But granting clemency to people who may not have committed any crime would push the boundaries of presidential pardon power, experts say.

The U.S. Supreme Court has described the pardon power as “the benign prerogative of mercy,” says Austin Sarat, a political scientist at Amherst College. But now, he says, “We’re in a virtually unprecedented period in American history.”

Pardons would shield people from defending themselves against the Trump Justice Department. But that’s different, experts say, from a process – open to anyone in federal prison – that is intended to correct wrongs inflicted by the justice system.

The Biden administration is reportedly considering pardons for people who could become targets of the U.S. Department of Justice during the second Trump administration.

The news, included in a Politico report last week, comes a week after President Joe Biden pardoned his son Hunter, who was convicted earlier this year of federal gun and tax charges.

The presidential pardon power is meant to be broad. But a preemptive pardon – one that covers crimes that people have not yet been accused of or that protects them from being charged if they haven’t committed a crime – is rarely used, experts say.

Why We Wrote This

As Donald Trump talks about prosecuting his political opponents, President Joe Biden could protect possible targets with pardons. Experts say America might be entering a new era of using this broad presidential power for political aims.

Those who favor President Biden’s use of preemptive pardons argue that unprecedented times call for unprecedented responses. So, while the United States rarely sees preemptive pardons, it may never have seen an incoming administration talk as much about retribution against its political enemies as this incoming Trump administration has.

Critics of preemptive pardons, meanwhile, argue that the answer to norm-breaking isn’t to break even more norms and permit future presidents to create impunity zones around them and their allies.

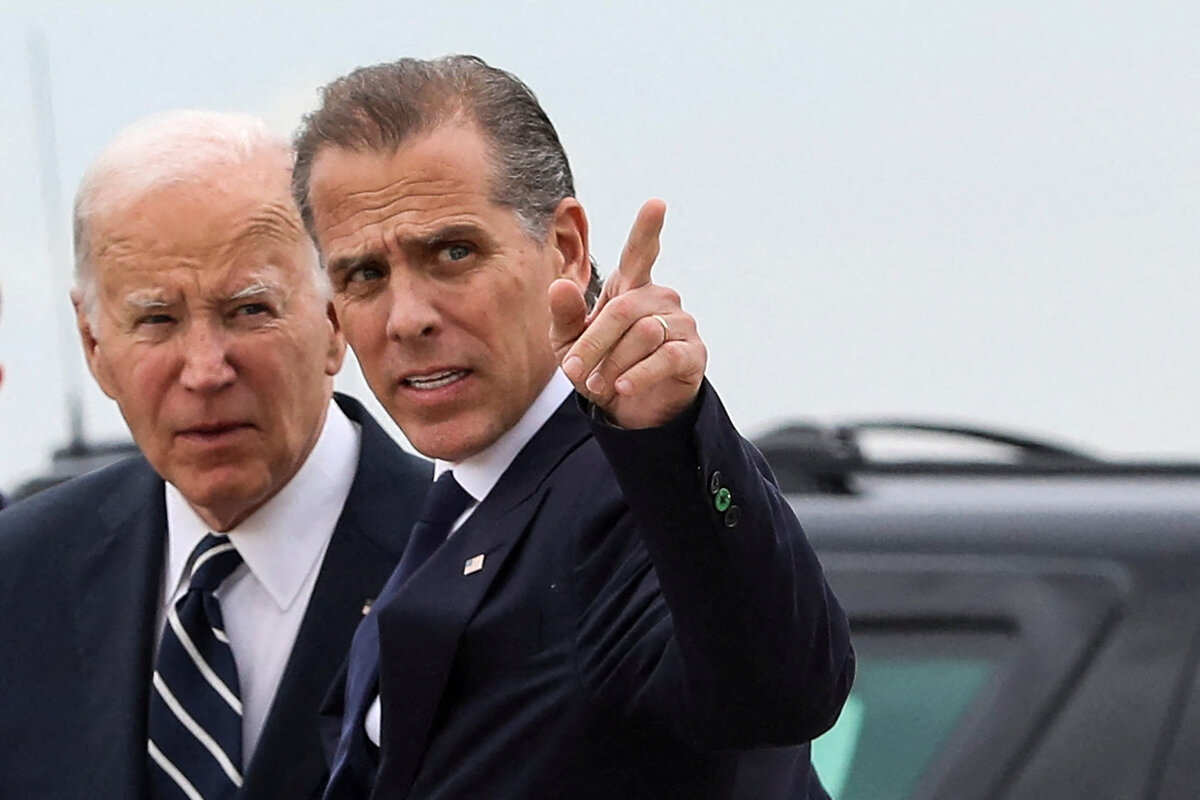

U.S. President Joe Biden stands with his son Hunter Biden, who earlier in the day was found guilty on all three counts in his criminal gun charges trial, after President Biden arrived at the Delaware Air National Guard Base in New Castle, Delaware, June 11, 2024.

“It’s never felt necessary or appropriate,” says Margaret Love, who served as the U.S. pardon attorney from 1990 to 1997. “It’s unmoored from [the pardon powers’] original ties to the justice system. Presidents have not thought about how to use this power in a democratic society fairly, accountably, for a lot of years.”

Pushing pardon boundaries

President Biden has already pushed the boundaries of the expansive pardon power. In last week’s pardon of Hunter, the clemency covered not just his son’s convictions but also any crime he may have committed during a 10-year period. Hunter has not served any time for his crimes. The only comparable pardon is Gerald Ford’s pardon of Richard Nixon after the Watergate scandal, as it protected Mr. Nixon from punishment for alleged crimes.

But granting clemency to potential targets of the incoming Trump administration – even though they may not have committed a crime – would push those boundaries even further, experts say.

Does the Trump era justify such a boundary push? In his first television interview since his reelection, President-elect Trump told “Meet the Press” that the congressional committee investigating the Jan. 6 storming of the Capitol should be jailed. The committee had been investigating efforts by his supporters to keep Mr. Trump in power; federal prosecutions of Mr. Trump’s own role in the efforts have been dropped in the past month.

Some of his nominees for high-profile law enforcement positions in his administration have made similar comments over the years. Pam Bondi, his pick for U.S. attorney general, said that “The prosecutors will be prosecuted, the bad ones,” in a 2023 Fox News interview, referring broadly to government lawyers who have brought charges against Mr. Trump. Kash Patel – the nominee to lead the FBI, the country’s top domestic police agency – appended a book he published in 2022 with a 60-name “enemies list.” Some on this list are likely under consideration for the Biden administration’s potential preemptive pardons.

J. Scott Applewhite/AP/File

Sen. Liz Cheney, vice chair of the House select committee investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, speaks at a hearing on Capitol Hill in Washington, Oct. 13, 2022, alongside Chairman Bennie Thompson and Rep. Adam Kinzinger. President-elect Donald Trump has suggested he will retaliate against committee members.

“Respect for democracy and the rule of law doesn’t mean that Joe Biden has to sit idly by and wait for the Trump administration to do things that he would regard as unjust and destructive,” says Austin Sarat, a political science professor at Amherst College.

In an early case about the pardon power, the U.S. Supreme Court described it as “the benign prerogative of mercy.” But Professor Sarat says the pardon power has come to be used less as an act of mercy and more as a tool to rectify injustice.

Preemptive pardons, by contrast, would not just shield individuals from potential prison time. They would also help deflect public censure, valid or not, and hefty legal expenses likely incurred defending themselves against the Trump Justice Department. Even preemptive pardons of the past have been justified as needed to achieve an essential public purpose, such as helping the country move on after a conflict. Two presidents – Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson – granted blanket pardons to former Confederate officers, for example, and President Jimmy Carter gave a blanket amnesty to individuals who dodged the Vietnam War draft.

Closing a troubling chapter or opening one?

Instead of helping the country close a chapter of its history, however, experts say preemptive pardons here could open a new and troubling one.

To start, issuing preemptive pardons could make the grantees look more guilty than some Americans already believe. Second, however broad the pardons would be, the Trump administration could still likely find targets for prosecution. Most importantly, Mr. Biden would be using the pardon power in a way that future presidents could abuse.

Using pardons “to protect one’s political allies prospectively just creates a really bad precedent,” says Frank Bowman, a professor at the University of Missouri School of Law.

Such a precedent becomes even more problematic following the Supreme Court’s presidential immunity ruling earlier this year, which grants former presidents broad immunity for official acts, he adds. Preemptive pardons would mean “All the people in the president’s orbit [could] do whatever they want during the term and get a pardon for it.”

That the Biden administration is even discussing preemptive pardons is disappointing, some experts say, and reflective of a lack of faith in the justice system’s ability to deter wrongful prosecutions.

It’s also reflective of how use of the pardon power has changed. Having issued the fewest pardons of any first-term president in history so far, Mr. Biden now seems focused on pardoning those who may not need that safety net. In doing so, he would be leaving others behind bars, like Leonard Peltier, a Native American activist now serving two life sentences despite high-profile calls for clemency.

Stephanie Scarbrough/AP/File

People gather for a rally outside of the White House in support of imprisoned Native American activist Leonard Peltier, Sept. 12, 2023, in Washington. Mr. Peltier is one of many considered candidates for a presidential pardon.

A more effective use of the pardon power would be to use it as it has been used for the past century – namely, to correct injustice and to broadcast a message of grace, mercy, and unity to the nation, experts say. That could come through pardoning someone like Mr. Peltier, as Democratic U.S. Sen. Brian Schatz of Hawaii has called for. Or it could come through commuting the sentences of the roughly 40 people on federal death row, as a growing campaign – reaching as far as the Vatican – is calling for.

There is also the possibility that preemptive pardons won’t be accepted. California Sen.-elect Adam Schiff, an outspoken critic and the lead prosecutor in Mr. Trump’s 2020 impeachment trial, has said he does not want a pardon. Liz Cheney appears undaunted by the prospect of being investigated.

“There is no conceivably appropriate factual or constitutional basis for what Donald Trump is suggesting – a Justice Department investigation of the work of a congressional committee,” she said in a statement on Sunday, describing his claims as “ridiculous and false.”

“Any lawyer who attempts to pursue that course would quickly find themselves engaged in sanctionable conduct.”