Books & the Arts

/

December 4, 2024

José Henrique Bortoluci’s What Is Mine tells the story of his country’s laborers, like his father, who built its infrastructure, and in turn its fractious politics.

While tending to his sick father as a pandemic ravaged their country, the Brazilian writer José Henrique Bortoluci wondered if he could “narrate the story of a society through the trajectory of a ‘common man.’” What Is Mine, the result of this undertaking, centers the life of Bortoluci’s father, also named José, and his 50 years driving a truck across Brazil as the country was shaped by the vicissitudes of its political leaders and mercurial economic fortunes. As “forests and rivers” gave way to “highways, prospecting, pasture, and factories,” the older José—affectionately called Didi by his family—left his hometown in the interior of São Paulo for the lonely expanses of rural Brazil, where his tales of adventure and friendship survived in fragments of memory. What began as the imperative to provide financially for his wife and two sons inadvertently became an involvement in one of the country’s most significant nation-building projects. Relying on his father’s patchwork recollections, the younger Bortoluci asked himself: “How do you narrate the life of an ordinary man?” And what does this narration say, not only about the son whose socioeconomic circumstances have cleaved so cleanly from his father’s, but also about the country whose national story consists of many such narrations and elisions?

Books in review

What Is Mine

by Jose Henrique Bortoluci; Translated by Rahul Bery

Buy this book

Now a sociology professor at the Getúlio Vargas Institute in São Paulo, Bortoluci grew up in a working-class family descended from Italian immigrants who’d arrived in Brazil in the early 20th century. Though What Is Mine is grounded in the life story of a truck driver, its form echoes an academic’s idiosyncratic experience of “the complex and unforgettable process of changing social class.” Weaving together intellectual, sometimes theoretical prose—which borrows from Susan Sontag, Audre Lorde, and Roland Barthes—and oral history, Bortoluci produces a text that not only marries his learned and inherited ways of knowing but also emphasizes their contradictions. “We can only speak our own language when we settle scores with the language of our parents,” he writes. The result is a unique mosaic of biography, political commentary, sociology, and critical history at once personal and national. This formal hybridity sets the stage for an exploration of how an ordinary man’s life—with its many nuances and hiccups—might illustrate the convoluted trajectory of a nation more accurately than one expects.

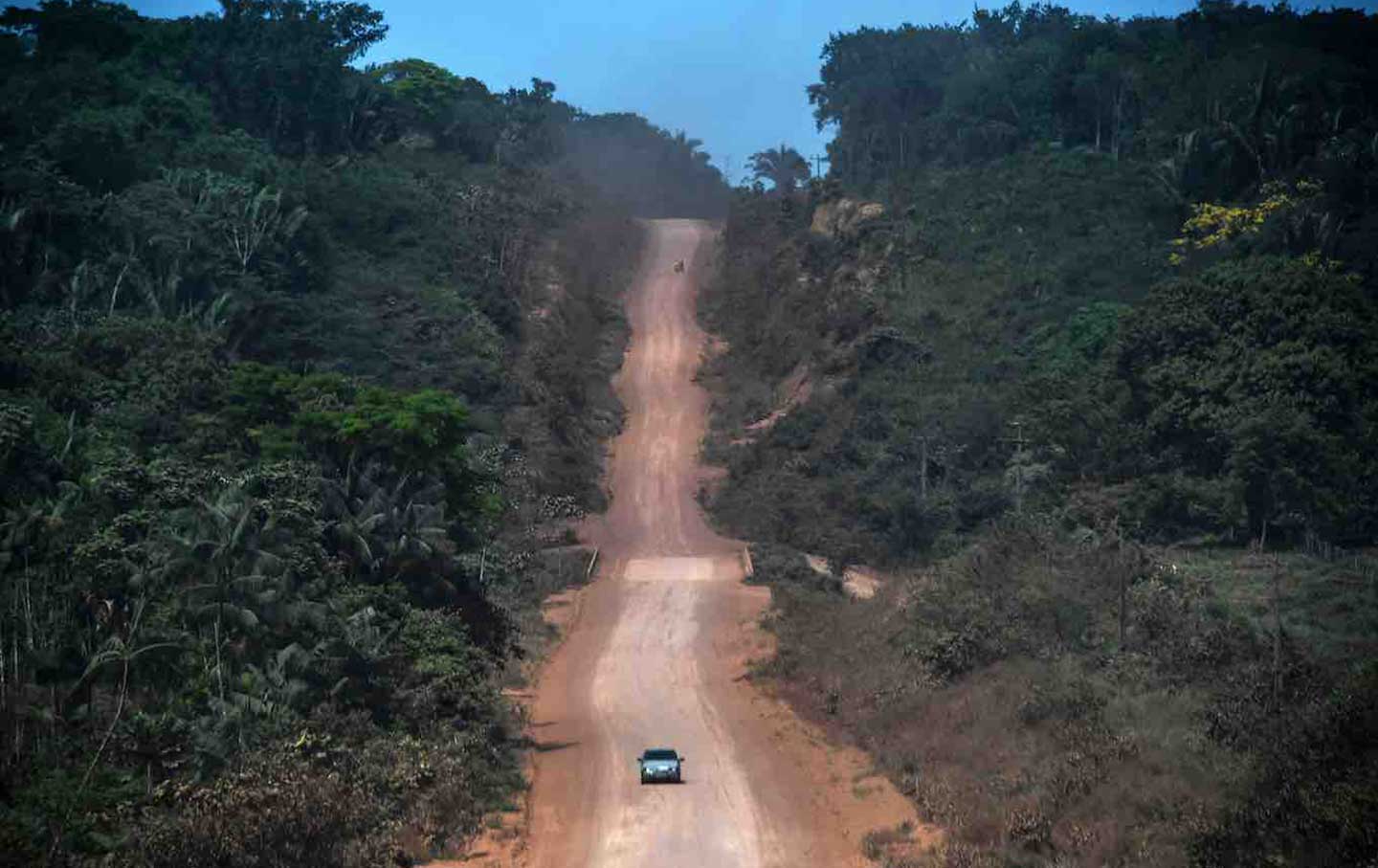

In a country that sprawls as widely as Brazil, the life of a truck driver is a notoriously grueling one of long hours—of “having to get up at two in the morning [and] driving till eleven-thirty, midnight”—and great physical and financial risk. For drivers like Didi, who started the job between the late 1960s and mid-’70s, when Brazil’s military dictatorship launched a series of reforms that precipitated a so-called “economic miracle,” working as a driver also entailed involvement in a nationalist dream that promised unprecedented levels of prosperity. Drivers took out large loans to purchase expensive vehicles in the hopes of establishing their own businesses. They took their trucks onto unpaved roads and pulled them through mudholes in untrammeled forests, traversing a country where large swaths of the infrastructure were yet to be built.

Bortoluci is unsparing in his criticism of the rapid economic development that occurred after 1964, when the Brazilian Armed Forces—supported by the US government—staged a coup against left-wing president João Goulart. In the 21 years that followed, the military regime enacted a series of major reforms and infrastructure projects aimed at increasing foreign investment and development. Though the process yielded as much as a 14 percent increase in national GDP by 1973, it also culminated in violent crackdowns on dissidents, high deforestation rates, and Brazil’s wealthiest 1 percent cinching almost a third of the country’s income by the end of 1985.

Of the regime’s various projects, perhaps the most notorious was the construction of the 4,000-kilometer-long Trans-Amazonian Highway. Connecting Brazil’s northeast to the Amazon region, the highway was designed to bring “the northeast’s ‘men with no land’ to the rainforest’s ‘land with no men,’” Bortoluci explains. In the highway’s wake, precious swaths of rainforest were felled and the Indigenous residents threatened, dispossessed, or killed; in these borderlands emerged a “sad opera of progress” in which land-grabbers, mercenaries, and illegal miners thrived and continue to proliferate to this day.

It becomes increasingly clear that Bortoluci’s project, a history of both his father and his country, envisions Brazil as a body being ravaged. After Didi is diagnosed with bowel cancer at the end of 2020, Bortoluci discerns that he cannot tell the story of Brazil’s political situation without interspersing it with details of his father’s illness. Unfettered capitalism and expansionism consume the nation’s resources in the ways that Didi’s body consumes itself.

Bortoluci’s main formal challenge lies in balancing two competing voices. As an academic and critic, he has the benefit of hindsight; as a son, he cannot help but confront Brazil’s history under the small shadow that his father’s presence has cast upon it. When Bortoluci speaks of the financial backers of the military regime, Didi remembers “Mr Camargo Correa, who was also from Jaú,” his hometown. When the writer laments mass deforestation, his father recalls the massive convoys of felled cherry, mahogany, and chestnut trees that he saw on the road, alongside the dried fish and bushmeat one could eat at the stalls set up for passing workers. When Bortoluci asks his father if he remembers “the ‘colonization’ of the northern region,” Didi’s answers “are always brief: I wouldn’t know what to say about that.”

Caught between these two distinct registers, the Trans-Amazonian Highway becomes both a “megalomaniac project” and “my dad’s road.” It is a contrast to which Bortoluci owes his career. He recalls his father’s reminder when he departed São Paulo to pursue his PhD in the United States: “Remember, your dad helped build this airport so you could fly.”

Familial inheritance develops an ambiguous edge in a story like Bortoluci’s, where a young person’s education distances them from the family that made such advances possible. Though much of Bortoluci’s politics is grounded in theory (the chapter on the country’s economic development begins with a disquisition on Marx), the intimate experience that undergirds his politics begs an approach that casts the theorizing aside. Rather, his politics is one of listening. It wants to know about the mudholes. It knows when to “say nothing,” as Bortoluci does when he admits that he cannot fathom the Brazil that emerges from his father’s stories using his “academic vocabulary.”

The book’s title stems from a statement by Didi that captures the challenge of writing anyone’s life story: that “only I can face up to what is mine.” Bortoluci interprets this as an admission of freedom from an older man confronting a life that has not been recorded in words other than his own. But even when Didi’s words are translated, first from the oral form to written text, and now from Portuguese into English, the inevitable changes challenge the belief that readers can hear Didi’s raw voice in his son’s prose. (One of the greatest challenges of translating What Is Mine, according to its translator, Rahul Bery, was rendering the colloquialisms of Didi’s speech into an idiom that felt believable in English. Though the original Portuguese captures the idiosyncratic texture of Didi’s verbal constructions—shortening fomos, or “we went,” to fomo, for example—it is smoothed out in translation.)

There are three chapters in the book told exclusively in Didi’s voice, narrating the stories of three distinct men that the older Bortoluci met and befriended on the road. Nestor, Manelão, and Jaques are friends with whom Didi witnessed the roadside purchase of drunken monkeys, several imprudent jokes that ended in a terrifying car chase, and an alleged extraterrestrial sighting one pitch-black evening in Mato Grosso. They are part of the cast of “forgotten heroes” who helped to build Brazil. But they are also semi-fictional constructions, their names pseudonyms and their stories composites of different tales that Didi told Bortoluci during their interviews. Decades after his father and his friends helped lay the foundations of modern Brazil, Bortoluci has developed an interpretation of recent history that goes beyond the usual narratives of how the country was built. He does so with the flair of invention; it’s a formal decision that suggests the instability of all narratives. As the laborers who built Brazil take their unrecorded stories to the grave, Bortoluci ensures that the history they lived and died by is not only kept alive but also levels the state-sponsored narratives one receives.

Since the reelection of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in 2022, the environmental devastation that occurred during Jair Bolsonaro’s presidency—when large-scale deforestation of the Amazon reached a 15-year high—has abated. But anxieties over history’s repetition loom large. Environmental activists breathed a sigh of relief when a license that Bolsonaro signed to upgrade the BR-319 highway, a tributary of the road that Didi helped to build, was suspended in July by a federal judge. But in September, Lula announced that his government would indeed finish the road as record droughts affect mobility along the Amazon’s rivers. While some, like Lula, believe the construction will be necessary for Brazil’s economic health, others—including ministers in his own government—fear that it will further entrench the “sad opera of progress” in which violence reigns in newly accessible, but poorly governed, areas. It is clear on which side of the debate Bortoluci would land, though his manner of situating himself offers a model from which we might learn.

After its publication in Brazil with Fósforo in 2023, What Is Mine entered its first reprint within a month of its release and was selected as one of “the best books of the year” by Quatro Cinco Um, a leading literary magazine in Brazil. Its publication with Fitzcarraldo Editions is one of 11 translations of the book in the last year. For all its focus on the language we use to tell our stories, What Is Mine has received wide acclaim for its reflexive honesty—a tone not often struck in the black-and-white narratives that feed political polarization not just in Brazil but in the world writ large.

In narrating the recent history of his country alongside the life of his truck driver father, Bortoluci gives us a bird’s-eye view on national history as informed by one man’s lived experience. In doing so, he foregrounds the dilemma of form and genre associated with such a task. To what extent is our understanding of national history a narrative informed by our own origins, class background, upbringing, and education? Why do such considerations matter? By asking these questions, Bortoluci achieves something unique in his retelling of Brazil’s 20th-century boom. His project teaches us that to study history demands more than abstraction and generalization. It requires an empathy that encompasses even those experiences we have never had, such that, in our admittedly limited imaginations, we will know how to advocate for one another—and to use the languages we don’t just inherit but are constantly learning for ourselves.

Jimin Kang

Jimin Kang is an England-based writer. She has previously reported on race and politics in Brazil with Reuters and published essays and fiction in outlets including The New York Times, Joyland, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and The Kenyon Review.