[ad_1]

With major policy disruptions — structural changes like the goods and services tax (GST), demonetisation, and an insolvency law (with last month’s amendment) — and big economic governance tools (recapitalisation of banks, and greater order through a transparent auctioning of natural resources, disinvestment and steady economic growth) behind it, Finance Minister Arun Jaitley, in the Modi government’s penultimate election Budget, puts the policy upheavals of the past three years together. Budget 2018 picks up the pieces of this apparently random policy jig-saw and binds it into a political economy narrative. This is a politically-sensitive Budget that consolidates past policies but also looks at and invests in a new future for the Indian economy.

The consolidation has two parts. The first captures the gains of the past. A 29 percent jump in the number of new taxpayers to 8.6 million in one year is no mean feat. Nor is the 28 percent increase in the number of effective taxpayer base to 82.7 million in two years. These are the benefits of demonetisation. Likewise, the formalisation of the Indian economy is now visible: Although the GST was ushered in only on 1 July 2017, the process of entering the tax system has been “massive”. Both these policies use technology and finance to make tax evasion a risky business. Catalysing these are banks, with their balance sheets now powered by bonds worth Rs 80,000 crore. The gains from these policies are now being consolidated on two large and troubling frontiers in Budget 2018 — agriculture and infrastructure.

In agriculture, the direction is towards doubling farmers’ incomes by 2022. That is, to step away from production-centric policies to productivity-focussed ones. With the minimum support price of most Rabi crops engineered to deliver a 50 percent return on investment to farmers already in place, Budget 2018 transposes it on the rest of the crops for the Kharif season as well. But prices are only one component of returns. Often, it is the middlemen, the traders, who pocket the benefits meant for farmers through the statutory agricultural produce market committees (APMCs) set up by state governments. Lack of access prevents small and marginal farmers who comprise 86 percent of all farmers from getting the benefits meant for them.

By linking technology and trading portals e-NAM (electronic national agriculture market) to create platforms for transactions, Budget 2018 proposes to offer small farmers the facility to make direct sales to consumers and bulk purchasers. This is part of a long evolutionary process that would give lower prices to consumers and higher returns to farmers. Being under the control of state governments, however, its success will depend upon on-ground execution in local mandis rather than in statements of a Union Budget document.

As far as Budget 2018 goes, the focus on agriculture is sending out a sharp political message too. The message is: ‘Dear farmers, the BJP has plans of prosperity for you.’

The first big test of this message will come in April-May 2018, when Karnataka goes to polls for 223 Assembly seats, and which will be a hugely-contested electoral battle. Before this, three smaller states — Meghalaya, Nagaland and Tripura, with 60 seats each — will have elections, soon after the Budget, in February-March 2018. The end of the year will see elections in another small state, Mizoram, in October-November 2018 for 40 seats. In 2019, as many as 11 States will have elections. This is not counting the big one — the Lok Sabha elections. Each of these elections will be hard fought.

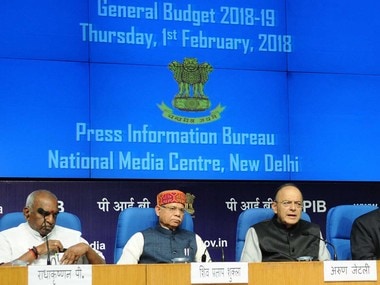

Finance Minister Arun Jaitley addresses a post-Budget press conference in New Delhi. Image courtesy: PIB

The success of BJP will, consequently, depend on the delivery of agricultural policies, particularly in ensuring farm incomes rise. This will be a double-edged sword: If incomes rise, votes may follow; if not, they will definitely go the other way. The agrarian focus of Budget 2018, therefore, contains high risk as well as potentially high returns.

Coming to infrastructure, the journey will be steeper, given the huge monies involved. Budget 2018 estimates it to be Rs 50 lakh crore, though other approximations place the number as high as $1.5 trillion or Rs 95 lakh crore. Making matters worse is the complexity of contracts in the sector, which have ensured that allegations of corruption and nepotism accompany almost every closure. It would be wise to remain cautious about their execution at such a large scale. Again, since the devil of “make or break” lies in delivery, we hope technology would be able to resolve much of these pains, given, of course, that the policy path is clear in one sector after another, from roads and ports to railways and airports.

It would be the same story of past caution and future technology hopes around building cities. Of the Rs 200,000 crore outlay for 99 Smart Cities, for instance, projects worth only Rs 2,350 crore or 1.2 percent have been completed, while Rs 20,852 crore or about 10.4 percent are under progress. True, speed kills and often breeds corruption, a malaise this government has remained far from thus far. So, the slower speed may express circumspection rather than inertia. Further, unless executed with a new round of political enthusiasm and administrative energy, bundling tourism into the cities programme is a yawn — every minister in every government has attempted to turn tourist cities into revenue streams and failed. Will Budget 2018 be able to change this? Unless the accumulated good intentions of the past 70 years come together and convert themselves into action, this will remain a grand strategy that would be read, analysed and repeated but not executed.

There are changes in taxation that will deliver outcomes. Firstly, the extension of a 25 percent corporate tax rate to companies with a turnover of up to Rs 250 crore. This will positively impact 99 percent of all companies filing tax returns (in his previous Budget, Jaitley had given this benefit to companies with turnovers of up to Rs 50 crore or 96 percent of all companies). Jaitley hopes this will nudge beneficiary companies into investing and creating jobs, neither of which is pre-ordained. But the relief being provided to small companies is real and tangible. More than money, this relief can be seen as an incentive to go legit, to pay taxes and to help them negotiate the “losses” from two digital enablers of a formal economy — demonetisation and GST.

The Rs 7,000 crore of revenue foregone on this count will be pulled out of Jaitley’s second change, the reintroduction of long-term capital gains tax on equities and equity mutual funds, from which he hopes to garner Rs 20,000 crore. All capital gains till 31 January 2018, however, will be grandfathered.

The justification for a long-term capital gains tax is terribly weak: “Return on investment in equity is already quite attractive even without tax exemption.”

Through this statement, Jaitley is implying that these gains will remain attractive in the future too. That is not possible unless the Indian market becomes an unrelenting outlier, beating all past valuations and going in only one direction, up. What Jaitley is not seeing is the other side of returns — risk. What he should have done instead, and which Parliament must debate and push for, is to increase the definition of “long-term” for equities to three years from 12 months, as in real estate.

On the income taxes front, barring two tiny changes, Budget 2018 delivers what it must — status quo. That is, no change in either the rates of taxation or the slabs on which they would be applicable. Jaitley, however, has reintroduced standard deduction — which former Finance Minister P Chidambaram had removed 12 years ago, in Budget 2005 — of Rs 40,000, for salaried taxpayers. This, he says, brings a little balance between the salaried taxpayers and the business or professional taxpayers (in 2017-18, 18.9 million salaried taxpayers paid an average of Rs 76,306 as taxes, while 18.8 million business or professional taxpayers paid an average of Rs 25,753). The number of Rs 40,000 is about 26 percent short of the Rs 50,553 differential. The effective savings will be statistically insignificant, but nobody’s crying.

In a small way, Budget 2018 is shifting India towards a future that has already happened, to embrace a forthcoming digital life. By tasking NITI Aayog to launch a programme that brings India at par with the global economy in general and artificial intelligence, machine learning, internet of things, block chain technologies, 5G and 3D printing in particular, it is powering extant schemes like ‘Digital India’, ‘Start Up India’, and ‘Make in India’ with knowledge. What India needs is an ecosystem that nurtures innovation, ideas and products that match the best in the world. This ecosystem can also work to strengthen the country’s defence system and catch up with the leaders — notably, the US, China and Russia.

The days of Budgets being policy statements and media events are over. Budget 2018 does what it is supposed to: Balance the books; the fiscal deficit target of 3.5 percent for Financial Year 2018 and 3.3 percent for Financial Year 2019 are in the right direction, give or take — while driving growth.

With its focus on farmers and the poor (the National Health Protection Scheme that would cover 500 million citizens in 100 million vulnerable households with a health cover of up to Rs 5 lakh for secondary and tertiary care hospitalisation), its politics is clearly aimed at the 17 state elections over the next two years and the 2019 general elections.

The article originally appeared in Observer Research Foundation

[ad_2]

Source link